June

2016

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

14

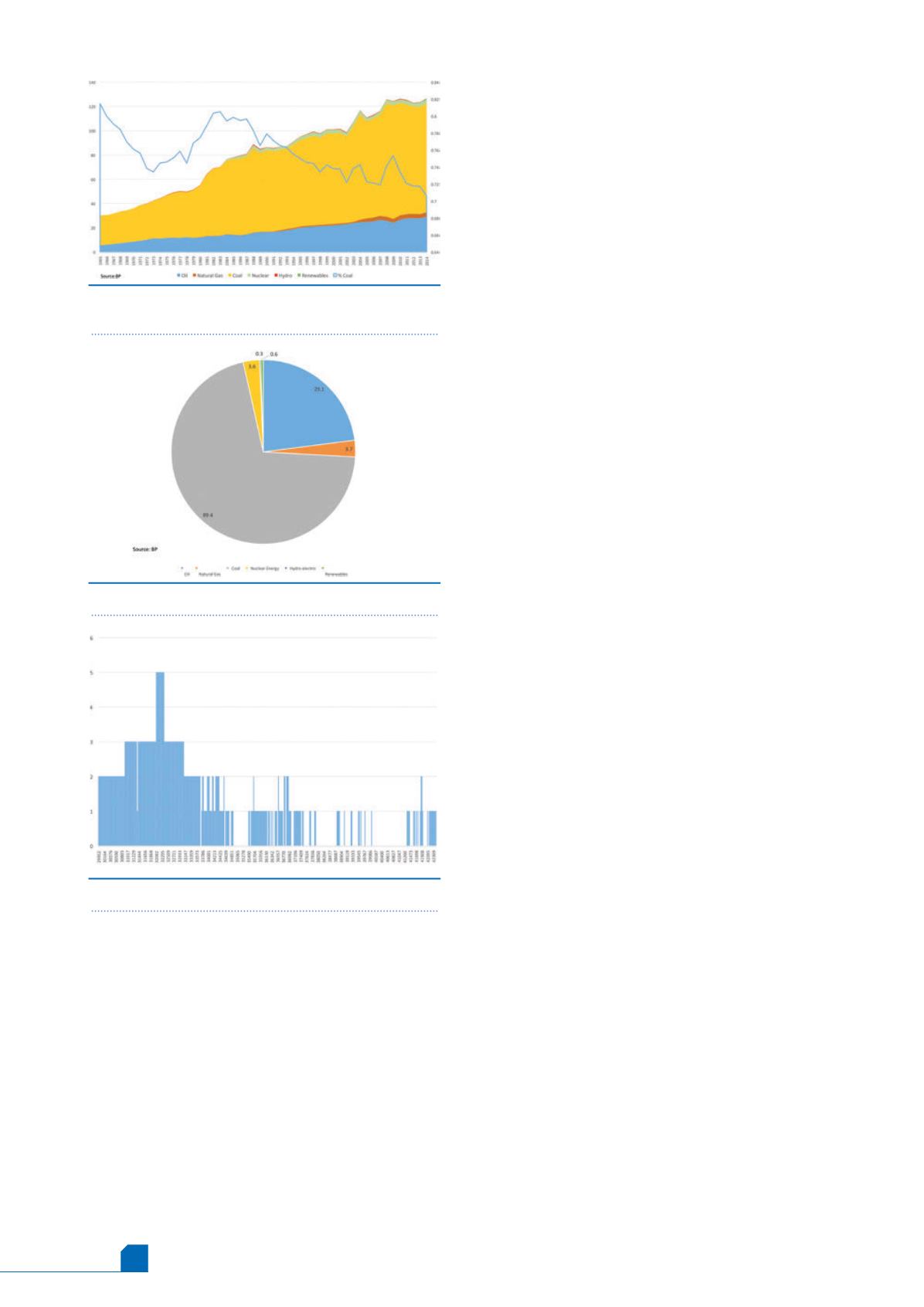

Figure 2 presents a look at the breakdown of fuels in the

primary energy mix, according to BP: coal supplied 70.6%, oil

supplied 23%, natural gas and nuclear energy supplied 2.9%

each, renewables supplied 0.5%, and hydroelectric power

supplied 0.2%.

Coal, oil, natural gas and shale gas

reserves

The Oil and Gas Journal, in its ‘Worldwide Report’, places

South Africa’s oil reserves at 15 million bbls. This amounts to a

mere 0.12% of Africa’s estimated oil reserves, and a vanishingly

small percentage of global oil reserves. The Oil and Gas Journal

estimates that current crude production is 3000 bpd.

South Africa’s natural gas reserves were listed as zero, though

the country does produce natural gas and is known for its

pioneering role as a gas to liquids (GTL) producer. Coal reserves,

in contrast, as estimated by BP, stand at 30.15 billion t, amounting

to 3.4% of global reserves, and having a reserves to production

ratio of 116 years.

South Africa’s government began searching for oil and gas in

the 1940s, under its Geological Survey of South Africa. The

government formed Soekor Pty Ltd in 1965 to oversee

exploration and development. Prospecting in the onshore areas

of the Karoo, Zululand and Algoa basins proved disappointing.

The government passed its Mining Rights Act in 1967, and it

granted offshore concessions to a variety of international

companies. The first offshore well was drilled in 1969.

Superior Oil discovered natural gas and condensate in the Ga-A1

well in the Pletmos Basin.

In the following years, South Africa’s Apartheid system

caused increasing internal resistance, strife and violence. The

international community ramped up its opposition to

Apartheid, beginning with bland diplomatic statements, but

gradually adding teeth by instituting arms embargoes and other

sanctions. South Africa largely became a pariah nation, and

international oil companies gradually left. Many investors

divested their holdings in South Africa. During those years,

Soekor explored alone, and with little success. The end of

Apartheid came in 1991, though most historians place the

effective date at 1994, when the first multi-racial elections were

held. The offshore areas were opened to international

companies in a new licensing round held in 1994.

Re-entering the international community stimulated

interest in South Africa’s oil and gas industry. The government

established a new state oil company, known as the Petroleum

Agency South Africa, in 1999. A new state oil company was

formed in 2001 via the merger of Soekor and Mossgas, known as

PetroSA. A newMineral and Petroleum Resources Development

Act was passed in 2002 and enacted in 2004.

The country’s oil and gas reserves are located primarily

offshore in the south portion of the country in the

Bredasdorp Basin and off the west coast of the country along

the border with Namibia. The offshore area near Namibia

includes the Orange Basin, believed to hold significant oil and

natural gas reserves, but these are not yet fully prospected or

commercial. This includes the Kudu gas field, which was

discovered long ago, in 1974, by a consortium including Soekor

and Chevron. Development and a pipeline to the coast are still

under consideration.

The advances made in hydraulic fracturing in the US

prompted countries around the world to assess shale oil and

shale gas potential. In 2013, the US Energy Information Agency

(EIA) published a report on shale resources, and South Africa

was noted as possessing the eighth largest technically

recoverable shale gas resource in the world. The EIA originally

estimated the reserves to be 485 trillion ft

3

, but later revised the

estimate down to 390 trillion ft

3

to reflect a downsizing of the

prospective areas. The shale gas resources are located in the

Karoo Basin in three formations known as Whitehill

(211 trillion ft

3

), Prince Albert (96 trillion ft

3

) and Collingham

(82 trillion ft

3

).

The public had many environmental concerns over the

potential development of the shale gas resource, largely over

the heavy demands that hydraulic fracturing places on water

resources. The South African government responded by placing

a moratorium on shale gas exploration until the impacts could

be considered. A government funded study later recommended

that the moratorium be lifted, and this was carried out in

September 2012. In October 2013, the government issued new

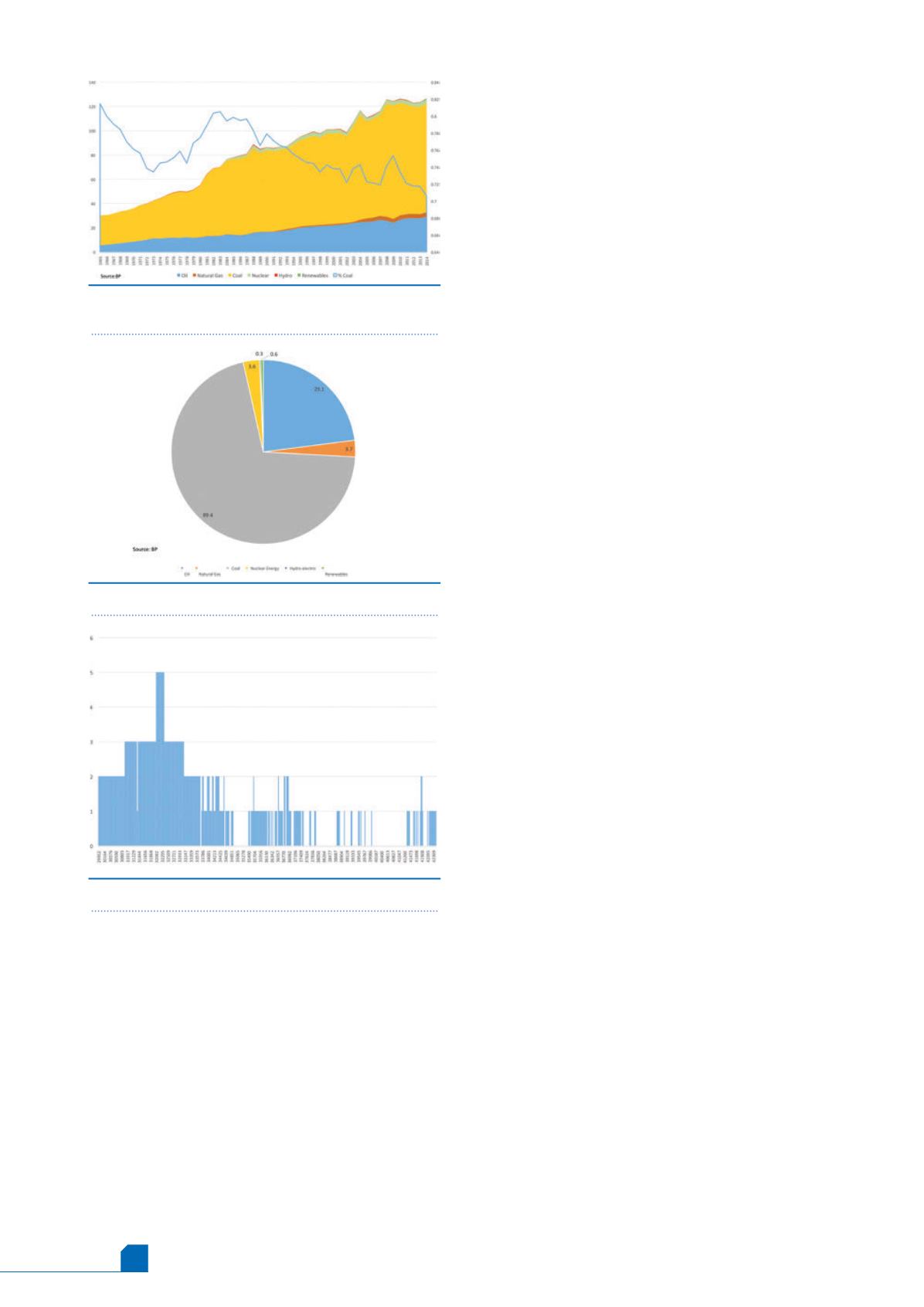

Figure 1.

South African primary energy use by type in

million toe.

Figure 2.

South African primary energy use.

Figure 3.

South African rig count.

Source:BakerHughes