June

2016

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

16

technical regulations governing oil and gas exploration,

particularly shale gas exploration and hydraulic fracturing. A

year later, the Petroleum Agency of South Africa (PASA)

announced that it would begin processing the existing

applications for exploring the Karoo Basin, though it would

not seek or accept additional applications. This timing

corresponded with the Saudi Arabian decision to stop

supporting crude oil prices, and global energy prices have

plummeted since then. Although South Africa has undertaken

energy projects that, at the time, seemed to be uneconomic, it

would be surprising in today’s market to see large scale shale

gas hydraulic fracturing developments go forward. Another

period of high energy prices, however, could spur renewed

interest, given the size of the reserve base and South Africa’s

expertise in Fischer-Tropsch processes.

Oil and other liquids production

South Africa’s upstream sector is organised under the purview

of its national oil company PetroSA. The key commercial oil

and gas fields include Oribi, Oryx and Sable, though these are

mature and largely played out. Oribi and Oryx are currently

not producing, and the Sable field, now known as the E-CE gas

field, is producing natural gas to supplement feedstock for the

Mossel Bay plant, which is PetroSA’s synthetic fuel refinery

(described in more detail in a following section). Slightly to the

east, the F-A gas field produces gas and condensate as feed for

Mossel Bay also.

Figure 3 provides the active oil rig count for South Africa,

as tracked by Baker Hughes. At the height, there were only five

active rigs working in South Africa. In more recent years, there

have been only one or two rigs, or none as production came

on and off. As of January 2016, there was only one active rig in

South Africa. Although over 300 exploration wells have been

drilled in the offshore area, plus 200 onshore, actual

production has almost vanished, and the current regime of

low crude oil prices has stymied additional work. A number of

offshore blocks have been awarded, however, to major

companies including Shell, BHP Billiton, ExxonMobil, Canadian

Natural Resources, Total, Anadarko, Cairn India and ENI.

Although South Africa historically has chafed at the idea of

being subjected to the constraints of the global oil price, it is

very much back in that position.

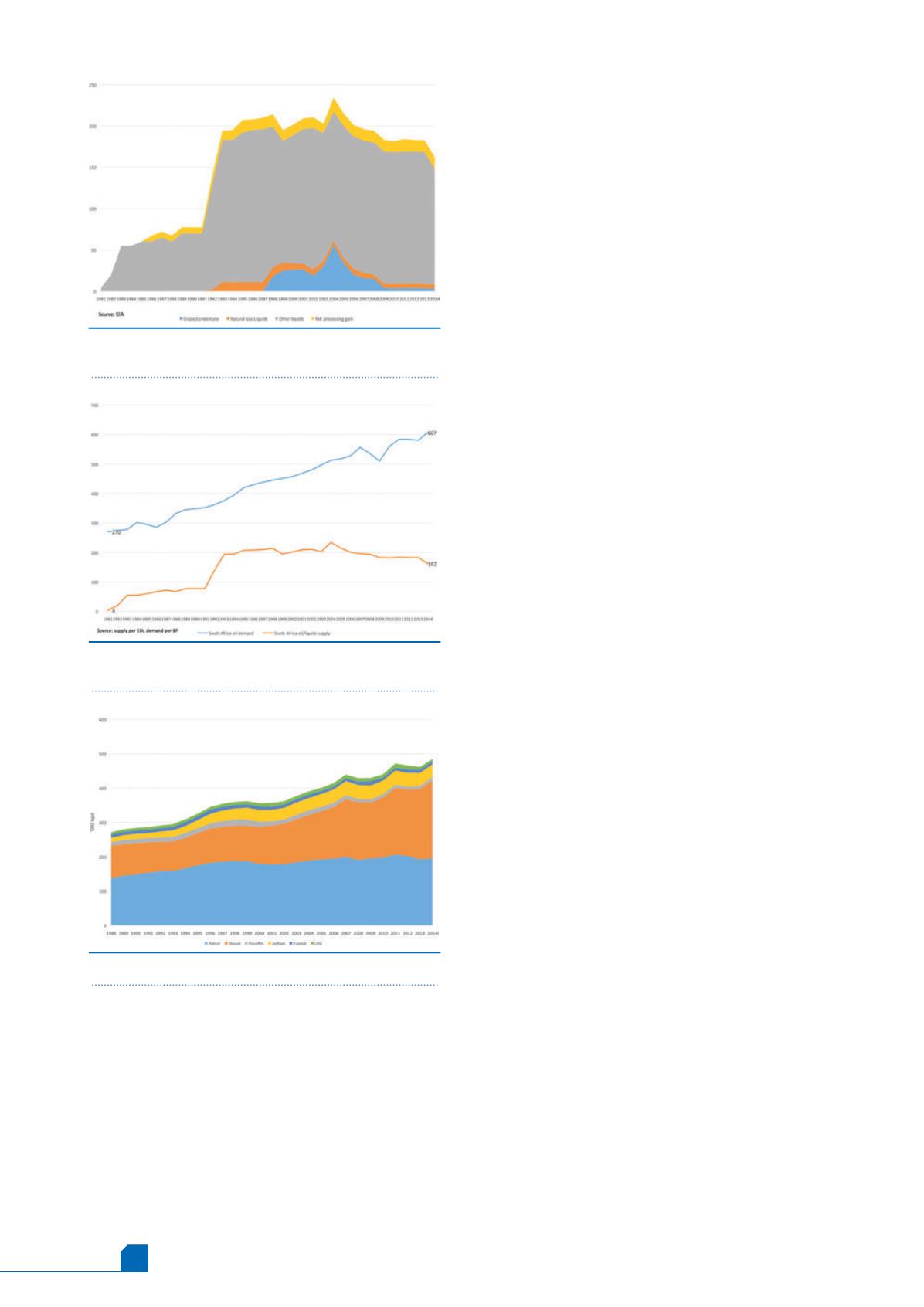

Figure 4 shows the trend in South Africa’s hydrocarbons

liquids production, as compiled by the US EIA. Natural gas

liquids (NGLs) began to be produced in 1991, and production

averaged 11 000 bpd from 1993 - 1998 before tapering down to

5000 bpd from 2008 - 2014. Crude and condensate

production commenced in 1998, averaging 18 000 bpd.

Production gradually ramped up to 54 000 bpd in 2004. But

this was the peak, and production fell to 34 000 bpd in 2005,

20 000 bpd in 2006, and it dwindled to a mere 3000 bpd in

2014.

Transforming coal to gas and liquids

The great majority of South Africa’s liquid hydrocarbon

production comes from its coal to liquids (CTL) and GTL plants.

Sasol is now known around the world as the pioneer of

commercial CTL production. Sasolburg and Secunda were built

atop massive coal deposits. The original CTL complex opened in

1955, long before the world began to have concerns over energy

supply security. The oil price shocks of the 1970s prompted the

construction of Sasol Two in 1980, and its twin Sasol Three in

1983. Sasol Two converts approximately 50 000 tpd of low

grade bituminous coal into a range of chemical and fuel

products. Sasol also added a high purity ethanol plant at

Sasolburg in 1990. In 1995, the first Sasol advanced synthol

reactor came online at Secunda, geared to increasing

production of light hydrocarbons such as olefins and synthetic

gasoline.

As Figure 4 shows, the output from Sasol Two started at

4000 bpd in 1981. It ramped up to 20 000 bpd in 1982. As

Sasol Three was commissioned, CTL output grew to 60 000 bpd

in 1985. Liquids production grew to 77 400 bpd in 1991 with the

completion of the ethanol plant, and another jump in output

was achieved in 1995 with the new synthol reactor.

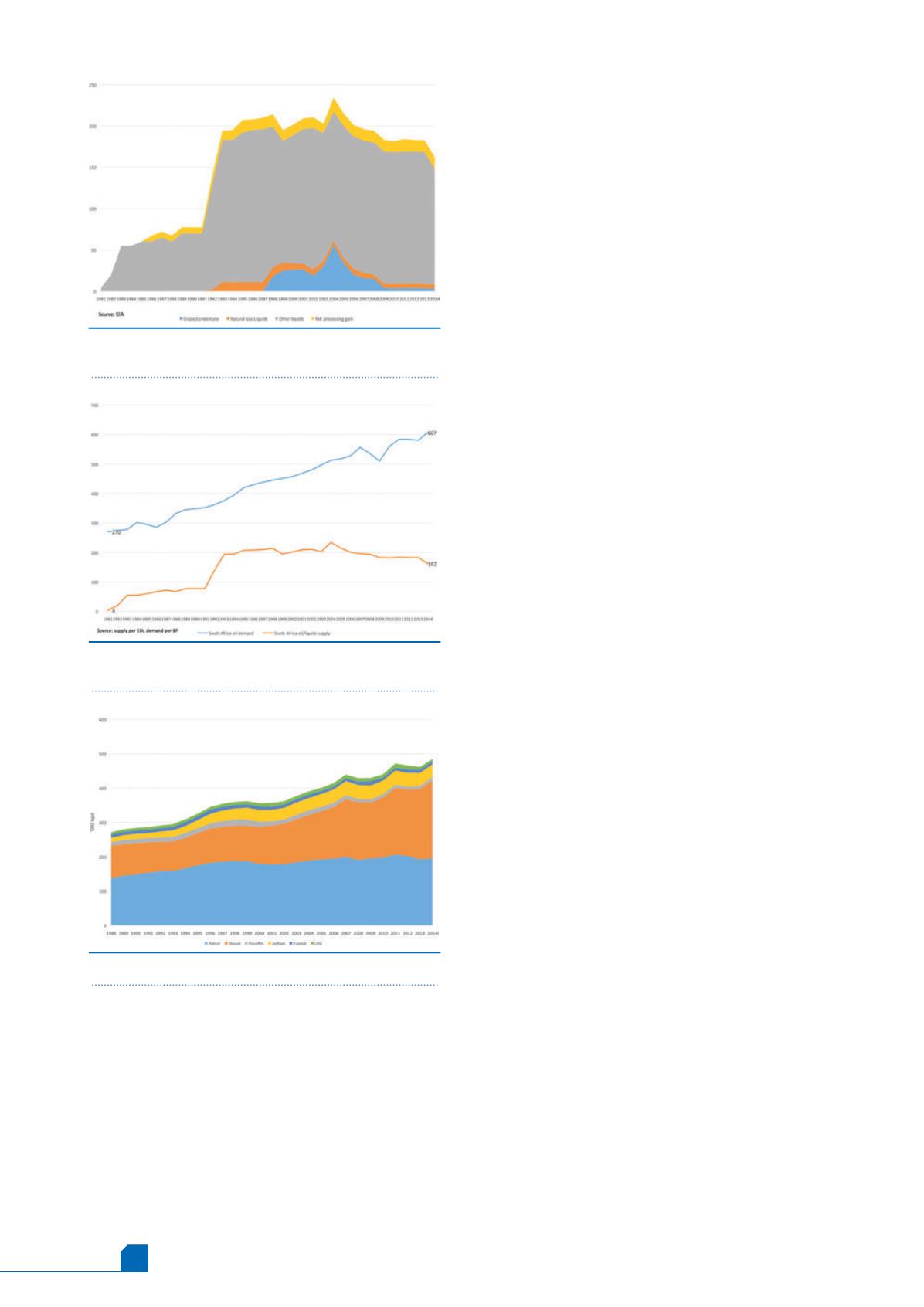

Figure 5.

South African oil demand versus oil and

liquids supply (000 bpd).

Figure 6.

South African petroleum product demand.

Source:SAPIA

Figure 4.

South African crude and other liquids

production (000 bpd).